The day was April 29, 2023, the start of Golden Week celebrations, on a sunny but still tolerably cool day in Nagoya City. I was running around the open space of the South Exit of Kanayama Station as a volunteer for the Philippine Friendship Festival (PFF). This event was returning for the first time since it was canceled in 2020 and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Sponsored by the Chubu-Philippine Friendship Association (one of the major volunteer groups engaging Filipino migrant communities throughout Central Japan), the event hosts multiple cultural presentations, Filipino food businesses, money exchange and transfer kiosks, as well as tourism booking booths. It’s an opportunity for Filipinos to meet each other, and promote Filipino places and points of pride to swarming Japanese crowds. I mostly assumed this was going to be my main concern for the day.

Something in the corner of the open space, however, caught my eye.

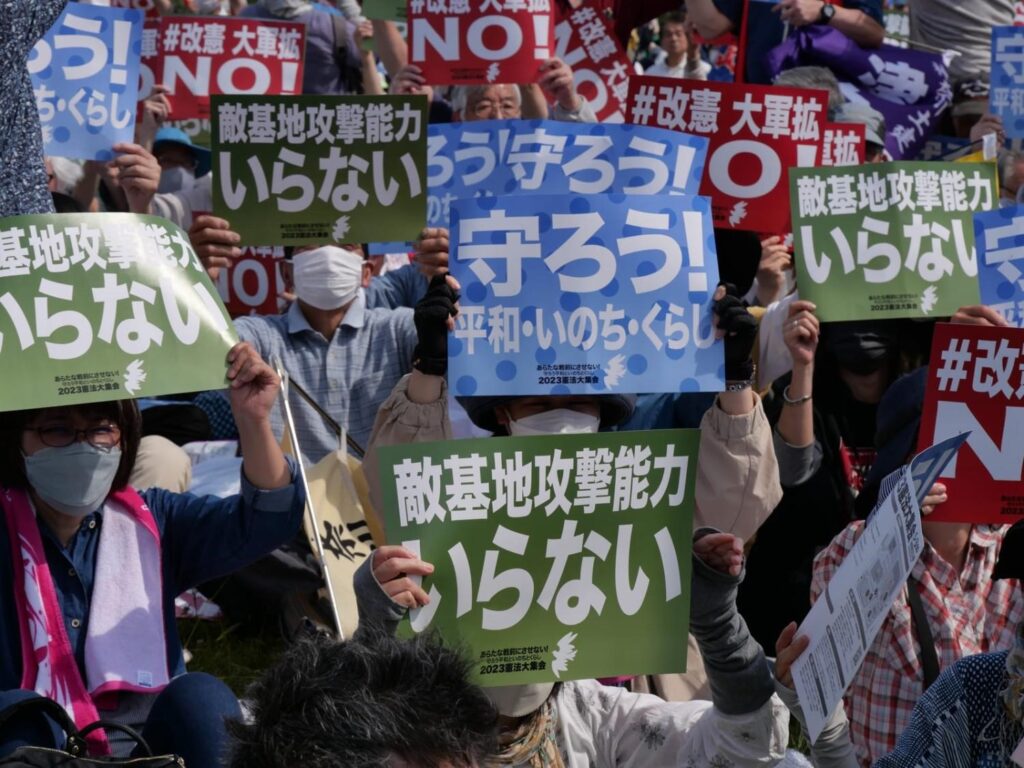

I encountered a handful of activists staging an impromptu call to action together with a mobile exhibit. Carrying posters, photos of protest actions, and political events, I realized the activists were members of Kenkoro (建交労, the All-Japan Construction and Transportation General Labor Union) protesting the government’s continuing subversion of Article 9 as well as campaigning for greater social spending.

Realizing that they were labor activists, I tried to converse with them—I with my limited Japanese and they with limited English. We were both pleasantly surprised to discover our connections—they are affiliates of Zenroren (the national Japanese labor movement) while I was a former labor center staff of SENTRO (a Filipino labor center that has had long-standing solidarity projects with Zenroren). They shared that Filipinos are among the well-known migrant workers in their fields and throughout this region, and were thankful to find someone like me who is sympathetic to them. They also reminded me of the occasional protest actions my activist friends, mentors and even former students staged when issues pop up. They tend to be a motley crew of no more than ten- or twenty-people holding placards, desperately gathering attention or trying to provoke a public response, with little success.

I did have to return to my volunteer work at PFF for the rest of the day (and they wrapped up not long after I left). That said, meeting them became an ongoing point of reflection for me since that day. I thought it quite sad that not only activist action here in Nagoya doesn’t seem to garner as much traction, but it seems to be a phenomenon wherever in the country. This is not to say that protest action in Japan in general remains unpopular or flat-out frowned upon—at least, not as much anymore. As discussed by Carl Cassegård in his 2022 article on the rebirth of Japanese protest movements, the twin factors of a) landscape changes that destabilized traditional Japanese politico-cultural regimes, coupled with b) the persistence of niche activist spaces that sustained progressive political attitudes even as they remain unpopular, are instrumental to reinvigorating civil society engagement.1

This is important considering Japanese civil society’s long sluggishness since the heyday of the Anpo (anti-US-Japan Security Treaty) in 1960 and the demise of the New Left in Japan in the 1970s. For the most part, protest action in Japan tends to mostly gain traction with the national audience if it involves three factors. The first would be if it is in response to monumental urgent issues like those in the aftermath of the 2011 triple disaster in Fukushima, the 2018-2019 protests against the corruption of prime minister Shinzo Abe (who was assassinated later), and the holding of Olympics in 2020. The second would be if the ones mobilizing are parts of minority communities pushing for integration/protection in Japanese society (such as those representing Zainichi Korean communities and the more recent #BlackLivesMatter Tokyo). Third, and perhaps more importantly, if the issues involved are covered globally and affect Japan’s international relations such as the ever-contentious Article 9 and the US bases in Okinawa.

Then again, maybe this is the core-periphery politics of many modern nations at work. Nagoya City, only recently catching up to the level of international attention and politico-economic significance of Japan’s other major urban centers (like Tokyo Metro and Osaka), exhibits the same challenges gentrified cities have when it comes to fostering more activist political participation. The consciousness or willingness of people to be part of a “community of fate” that would mobilize them towards open engagement remains alien to popular Japanese consciousness—booted and stigmatized as it was during the boom economic years before the bubble of the 1990s. Hence, it’s a bit unfair to expect it to sustain the same level of monumental activist changes that may be more visible in Tokyo Metro. The situation tends to affect civic and organized groups in general regardless of ideology, as not even the more conservative and right-wing mobilizations (such as uyoku dantai and anti-vaxxer groups) tend to garner enough boots on the ground either.

This brings me back to something I was directly tied to: the Filipino communities in Central Japan. While being part of volunteer and cultural exchanges is one thing, it’s another thing to ask about Filipino activism in Japan. If Japan in itself is still struggling with fostering more open and engaged spaces for Japanese of all ages to express their dissatisfaction and dissent at how their country is run, how does the Filipino diaspora figure in these niches? Should we agitate and engage? Should we reach out by means of international solidarity? Or do we keep to ourselves until our problems become big enough that it has to be aired out in the open? For that matter, to what extent are we actually seeking to engage and educate, or to merely “find our own”?

The answer, if my own experience of Filipinos’ engagement with the 2022 national elections back in the Philippines is any indication, depressingly suggests the latter.

Hansley A. Juliano is an LRI fellow engaged in writing about civil society & social movement history, as well as labor policy strategies. He is also a returning Lecturer of the Department of Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University. He is currently finishing his Ph.D. in International Development at the Graduate School of International Development (GSID), Nagoya University.

1 Carl Cassegård (2023), “The recovery of protest in Japan: from the ‘ice age’ to the post-2011 movements,” Social Movement Studies, 22:5-6, 751-766, DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2022.2047641.